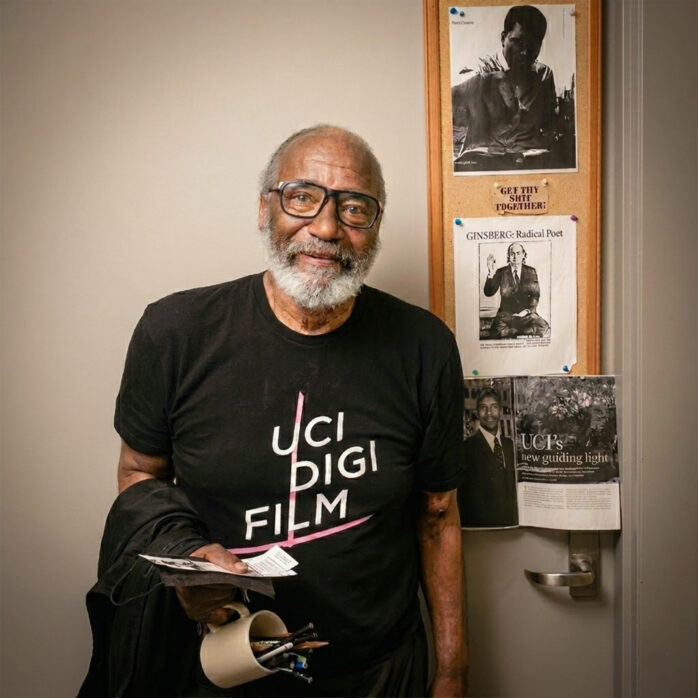

This was from the day Ulysses and I drove down to UCI to close up his office, a bittersweet moment that still stays with me. He had just retired after nearly three decades, stepping away, as it happened, at almost the exact moment the art world was finally giving him his due, with a major retrospective making its way in 2022 from Philadelphia to the Hammer. There was something very Ulysses about that timing: unhurried, unbothered by recognition that arrived on its own schedule. I can still hear Alice Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” playing as we looked over all that history that afternoon.

Those years at UCI were just one chapter in a remarkable career. Born in Los Angeles in 1946, Ulysses had been making video art since 1972, when the medium was brand new, picking up a Portapak when most artists hadn’t yet imagined what moving images could do in the hands of someone determined to tell different stories. Working as what he termed a “video griot,” he drew on oral storytelling traditions, structuring his work around music, poetic recitation, and dynamic performance to interrogate race, representation, and the power embedded in popular culture.

Part of what made him singular was how early he grasped what networked media could become. During the 1980s he worked with the Electronic Café, a grassroots arts group pioneering collaborative telecommunications that connected communities through interactive video, audio, and shared screens, accomplishing this decades before Skype and Zoom. Through his conceptual art band Othervisions, he explored the relationship between spoken word and lyrical content, and as artistic director of Othervisions Studio he brought that same Afrofuturist sensibility to an interdisciplinary practice that kept evolving for fifty years. He joined UCI in 1993 and spent nearly three decades shaping generations of students who went on to cite him as a foundational influence.

In the years that followed we got in the habit of having breakfast at Pann’s near his place every few weeks, as Ulysses became a regular part of my life. The staff adored him and always greeted him by name. I think the idyllic atmosphere of that diner was a kind of antidote to the exhausting ritual of dialysis that took up so much of his last few years. As we were sitting in Pann’s just a couple of days before he passed, he looked across the table and remarked, “This place. All these different kinds of people, together, getting along, in times like these. It’s so wonderful.” Never one to complain very much, Ulysses would often muse this way. He was one of the most relentlessly positive people I knew and at the same time one of the most brilliant. Celebrated in recent years for his visionary understanding of media and politics, Ulysses had that rare gift of intuiting novel ideas. As I was dropping him back at home that day, a different kind of mood hung in the air. Call it a premonition or something else, but I felt I had to tell Ulysses how much his friendship meant to me, both now and across the decades. Looking back now, I realize that he had been extremely frail that day. We even spoke about it briefly and he said he planned more walking. I guess I thought he would bounce back yet one more time.

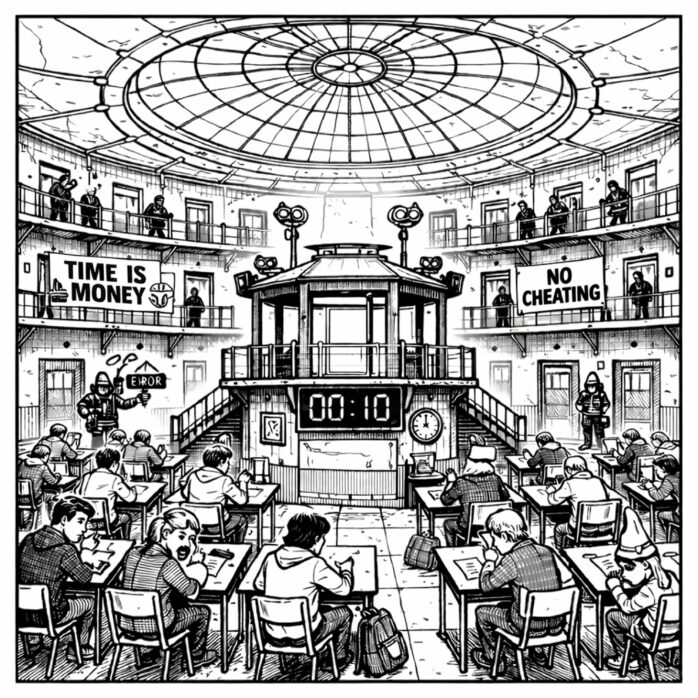

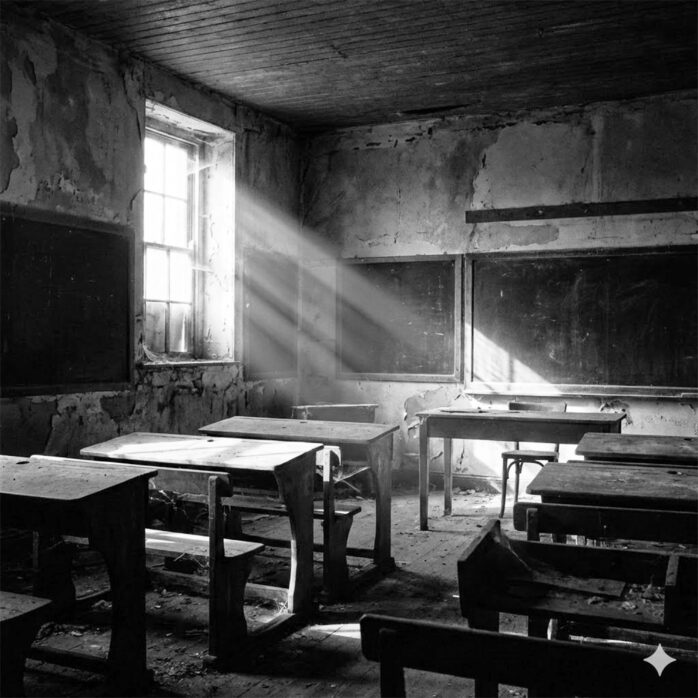

But once activity is translated into data, the data begin to influence the behavior they claim to measure. A brief pause can register as disengagement. Rapid typing can signal focus. Students eventually realize that unseen systems are interpreting their actions and may begin performing for algorithmic approval instead of thinking for themselves. What used to be an exchange between learner and teacher becomes a loop between student and machine. This shift matters because effort is no longer understood through experience but through metrics. In a traditional classroom, effort lived in rereading, revising, and wrestling with ideas. In digital spaces, it gets recorded as keystrokes, session length, and completion rates. These numbers are useful but incomplete. They capture what is visible and overlook what is internal. Confusion, insight, doubt, and breakthrough moments rarely leave a trace.

But once activity is translated into data, the data begin to influence the behavior they claim to measure. A brief pause can register as disengagement. Rapid typing can signal focus. Students eventually realize that unseen systems are interpreting their actions and may begin performing for algorithmic approval instead of thinking for themselves. What used to be an exchange between learner and teacher becomes a loop between student and machine. This shift matters because effort is no longer understood through experience but through metrics. In a traditional classroom, effort lived in rereading, revising, and wrestling with ideas. In digital spaces, it gets recorded as keystrokes, session length, and completion rates. These numbers are useful but incomplete. They capture what is visible and overlook what is internal. Confusion, insight, doubt, and breakthrough moments rarely leave a trace.