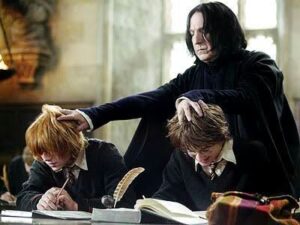

You’ve probably never heard of TestingMom.com. It’s part of a new generation of test-prep companies like Kaplan and Princeton Review –– except this one is for toddlers. Competition for slots in kindergarten has gotten so intense that some parents are shelling out thousands to get their four-year olds ready for entrance tests or interviews. It’s just one more example of the pressure that got celebrity parents arrested for falsifying college applications a few years ago. In this case the battle is over getting into elite elementary schools or gifted programs. While such admissions pressure is widely known, what’s new is how early it’s occurring. Equity issues aside, the demand to improve performance is being drilled into youngsters before they can spell their names. All of this bespeaks the competition for grades, school placement, and eventual careers that has transformed the normal impulse to do better into an obsession for students and their families. Much like the drive for perfection, an insatiable hunger to be quicker, smarter, and more acceptable to admissions officers is taking its toll in many ways.

It’s just one more example of the pressure that got celebrity parents arrested for falsifying college applications a few years ago. In this case the battle is over getting into elite elementary schools or gifted programs. While such admissions pressure is widely known, what’s new is how early it’s occurring. Equity issues aside, the demand to improve performance is being drilled into youngsters before they can spell their names. All of this bespeaks the competition for grades, school placement, and eventual careers that has transformed the normal impulse to do better into an obsession for students and their families. Much like the drive for perfection, an insatiable hunger to be quicker, smarter, and more acceptable to admissions officers is taking its toll in many ways.

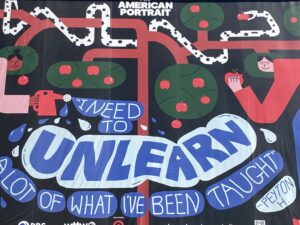

What explains this obsessive behavior? Brain science has been proving what advertising long has known –– that wanting something is far more powerful than getting it. School admissions and other markers of success are part of an overarching mental wanting mechanism. That new iPhone might bring a thrill. But soon comes the yearning for an update, a newer model, another purchase. Neuroimaging shows that processes of “wanting” and “liking” occur in different parts of the brain, with the former more broadly and powerfully operating than the latter. This reverses the common wisdom that primal hungers and “drives” underlie human motivation. Unlike animals, the motor force driving human beings is imagination –– with anticipation of something more important than the experience itself. This partly explains why merchandizing deals more with feeling than facts. Slogans like “Just Do It” and “Think Different” bear no direct relationship to shoes or computers, but instead tingle feelings of desire. In the fuzzy realm emotion pleasure is a fungible currency. Continue reading “The New You”