How do you live a “good life”? It’s a question philosophers have pondered and pollsters still pose. Answers vary a lot, given differences in opinion and the breadth of the issue. What often comes to mind is a definition of happiness or what makes a life satisfying. For most people, the question entails both “self-directed” aspects of personal experience and “other-directed” elements of one’s place among others.[i] Definitions of the good life can refer to abundance (“luxury, pleasure, or comfort”) or insight (“simplicity, health and morality).”[ii] Other qualities include freedom or the idea of life as a journey. This chapter explores how people view and pursue the good life, and what obstacles may stand in their way.

Discussions of the good life date to the ancient Greek concept of eudaimonia, a word commonly translated as “happiness,” “flourishing,” or “well-being.”[iii] Aristotle cast eudaimonia as an aspirational state that individuals could achieve by demonstrating authenticity and virtue in the eyes of the divine. This differed somewhat from the more immediate state of pleasure and enjoyment known as hedonia. As later philosophers gave people more credit for self-determination, enlightenment era figures like René Descartes and Baruch Spinosa linked the good life to a reasoned control of human passions.[iv] Christian interpretations of the good life sometimes gave it a moral character in beliefs that humans were created in God’s image, which is “good” by definition. In this line of thinking, virtue and success in life go hand-in-hand.

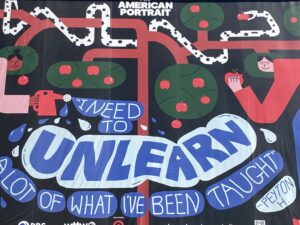

Historical figures sometimes made lists to define the good life. Socrates said such a life should follow five principles: temperance, courage, piety, justice, and wisdom.[v] Gautama Buddha spoke of an eightfold path of understanding, thought, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration.[vi] Almost all traditional good life lists had people conforming to widely held doctrines or belief systems, with the “self” cast as an element in a larger plan. In today’s more secular times most people see the good life as a matter of perspective. Unfortunately, this relativization has brought with it a certain emptiness. A simple online search for good life will provide you with a list of “bucket lists” of activities such as traveling or skydiving. Continue reading “The Good Life”